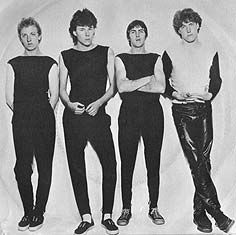

Rather fittingly, he shared a name with the technical term for the growing pains commonly found in young breed dogs. Because Pano was on board with the Dunfermline punk outfit The Skids while they were experiencing . . . well, growing pains.

Rather fittingly, he shared a name with the technical term for the growing pains commonly found in young breed dogs. Because Pano was on board with the Dunfermline punk outfit The Skids while they were experiencing . . . well, growing pains.Pano was the band's heid bummer for a bit. And honestly, how could he not be? He was a Hell's Angel from Fife, a pedigree that meant he was prone to dispensing a sound skull-thumping every now and then. One can imagine it was often in the defense of Ricky Jobson, The Skids' extroverted, ostentatious lead singer, who apparently was quite deft at raising the hackles of others. "I'd dyed my hair black and white," Jobson told Brian Hogg for his book, All That Ever Mattered, "and wasn't afraid to do anything."

During those early days, Pano flexed his managerial muscles, securing the band a rehearsal hall, landing gigs. The Skids debut took place at Bellvue in front of several hundred punk zealots. It was a nervous affair, Jobson on stage, a tattered piece of notebook paper in hand with his lyrics. U.K. punk shows had earned a deserved reputation for being a tad unruly. Did Pano need to size-up a lad getting too chippy with the fledgling act, bellow a "Ah'll stoat yer wallies," and then change from manager to enforcer with one thunderous punch?

We're not quite sure. While information on The Skids is quite plentiful, information on Pano is sparse. Thankfully, the music is still with us.

Hear it for yourself. Download: "Integral Plot" by The Skids.

Note: I conducted numerous Internet searches in an effort to track down more information on Pano. All I found was a summary on Google that read: "Mike Douglas (Pano) the Skids manager stayed with me though in Gardeners St. when the Skids first started, so the band were basically in and out of my house." However, the link to the site wasn't functional. Further searches involving the above name turned up nothing. Any further info regarding Pano would be appreciated.